I taught at a high school in Maryland for a year after college and during that time the school invited Betty Currie, Bill Clinton’s secretary, to speak to my American Government class, an event notable for two reasons. One was her telling the story of Dick Morris being caught “with those ladies of the night!” This was exactly the flavor of American Government that a room full of sixteen year olds was dying for, and with no training as a teacher myself, there was no hope of holding back the deluge of giggles. The other thing that I remember was that she thought Robert Reich was a very nice man.

Those two men, Reich and Morris, feature

in a brilliant documentary, Adam Curtis’s “The Century of the Self”. Reich’s

description of the adaptations the ever adaptable Bill Clinton, under the

influence of Dick Morris, toward focus group or marketing based politics is

well told and insightful. Reich was so clear about the confluence of politics

and marketing. I encourage you to watch it. But, when you get one thing right,

people pay attention; and it makes it even more important that you get other

things right, because now you have the power to lead. In spite of his niceness,

I think Reich is wrong. And really, when

I hear someone described as nice, I hear Zero Mostel in The Front when his

character says “It’s nice when nice happens to someone nice” just before

throwing himself out a window.

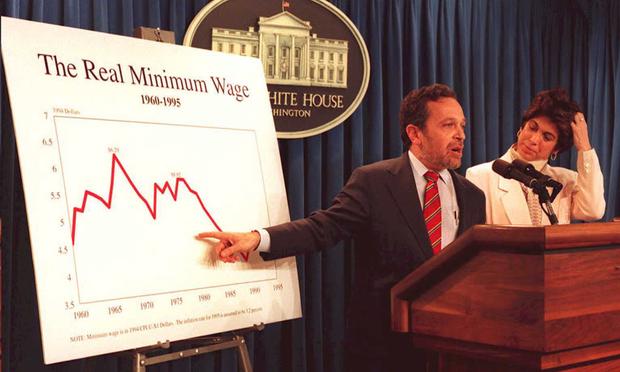

So recently I watched Inverness home

owner Robert Reich in his own documentary called “Inequality for All” that was

made in the style of Errol Morris’s brilliant “Fog of War”. With its parade of

black and white photographs of Reich with Bill Clinton and archival clips of

his press conferences, married to a minimalist musical score, the quotations

were eerily direct from Morris’s movie about the tortured conscience of Robert

McNamara. Indeed, it amuses me to think of Reich shouting at the editor, “More!

Make me more like McNamara!” More likely, we can put this down as a visual

storytelling shorthand that because of the success of the “Fog of War” has

become very common. While no historian would compare Reich and McNamara, there

are actual similarities between the two former members of Presidential cabinet.

It is in the way that we talk about our problems and how to solve them.

Our war on the Vietnamese is a monstrous

crime that haunts us till this day. McNamara himself put the number of

Vietnamese that Americans killed at 3,800,000. Less than a year ago a veteran

of that war, after forty years of nightmares like so many others, hanged

himself in Tomales. But it isn’t war crimes that Reich shares with McNamara, it

is that McNamara more than anyone else represented the idea that a modern and

sophisticated government would rely on the compilation and computation of statistics

and “systems analysis” to describe and solve the problems of our world. As

Secretary of Defense, he redefined the idea of the “serious” or “realistic” way

to talk issues: it isn’t about history or patriotism, realms of emotion and

subjectivity, it is about the numbers.

In his writing, Reich often tilts

against concentrations of wealth, but then, when he reaches the precipice of

insight, in fear of what lies beyond perhaps or in fear of not being thought “serious”,

he withdraws. And he begins to speak like McNamara, a technocrat, declaiming statistics

as though they had any power still to persuade. It is his desire to be seen a

serious thinker, to avoid platitudes, that we enter into this contemporary numerology

– so many per cent of this means so much increase in that.

How is he wrong? History, the story

of what happened and why. Robert Reich asks us to look back to the first

decades after the Second World War, to discover solutions to our present

problems. He says, to improve the world, we need to reduce income

inequality – such a modest phrase, such an obvious good. The problem is that it

doesn't suggest what we ought to produce through our labor or who should own

it. It just says: we need to pay people more, so that they can consume

more, and then the economy will take off. Setting aside how wildly

irresponsible it is to suggest that increasing "growth" and

consumption will solve the problems of a society poisoning itself to death –

via consumerism – let's look at one of his proposals specifically: we need

stronger unions, then we will all have the disposable income, therefore more

equality, that we need. He is asking us to be realistic. Don’t ask for the system to change, change

the balance within the system.

The union movement, thanks to

"realists" like Samuel Gompers and the Federal Government's violent

suppression of labor activists during various "Red Scares", moved

away from worker control of production and social transformation, toward a sole

focus on collective bargaining to increase the compensation of workers for their

labor. This led to unions in the post-war era, Reich’s golden age to which

we should return, whose members attuned themselves to a barren intellectual and

spiritual landscape. Unions stood for nothing except what a Teamster once told

was the attitude of "Pay me. Don't delay me."

For a while it looked like unions had made a good deal with corporations. Based on this blinkered history, he is not the only "realist" today speak of the amount of disposable income an individual has, or relative income inequality, as the statistic to focus on. So couldn't we just go back to the 1950s?

For a while it looked like unions had made a good deal with corporations. Based on this blinkered history, he is not the only "realist" today speak of the amount of disposable income an individual has, or relative income inequality, as the statistic to focus on. So couldn't we just go back to the 1950s?

The condition that created the

industrial boom of those years was the devastation caused by most destructive

war in human history, World War II, always treated as some disembodied event

and brushed over. In the aftermath, the unions made their peace with

corporations and the government. What they lost when they largely abandoned

anarchist, communist or socialist politics was the question of whether laborers

would be involved in the question of what they would build and to what purpose.

And while workers did enjoy short term prosperity after the war, because they

forgot or never were taught the historical and philosophical foundation that

unions were built upon during the early 20th century, when the boom time ended

they didn't get the either good monetary compensation and had no idea how to

construct an alternative to American empire and globalized trade.

Still,

talking about strengthening unions is considered modest, “realistic.” I

maintain it is outlandish as a response to the decline of our society. Let’s unionize

workers at Walmart or McDonald's, so that they can increase their pay, but isn’t

Walmart itself problem? This melanoma that blotches the map of America; this

swollen lymph node that indicates underneath a cancer of globalized trade that

undermines local producers and laborers and ensnares the world in making

garbage food and goods for slave wages then shipping them, at massive carbon

expense, to keep on life support the impoverished and demoralized citizens of

the new third-world country we have built within the borders of the United

States. That global trade policy (a parade of abbreviations in addition to

NAFTA: WTO, GATT, and now TPP, etc.) and its effects on workers, health,

climate and civilization generally goes uncommented upon is astonishing.

The Black

Death’s impact was so profound that chroniclers of the 14th century,

who recounted all the wars in detail, give it often only one short

mention. Indeed, it is said that a

society’s greatest madness is called “normal” and not seen at all. And while

these policies were so easily, if ruthlessly, implemented, realists like Reich tell

us, if only through his refusal to comment upon them, these treaties cannot now

be undone. Just as McNamara refuses to offer his opinion on his responsibility

for the Vietnam War (“I’d rather be damned if I don’t.”), Reich, Secretary of

Labor at the time of its passage into law, cannot utter five little letters,

NAFTA. They do not appear in his version

of “Fog.”

The union revivalists at least

approach the level of tragedy because they come from a tradition of the weak

standing together to make demands of the powerful. But what is the

demand? Just that the corporations just give a little of profits of global

collapse back to us! And then, when the minimum wage is $15, magic!

Americans are in a trap. First we gave up our ideas of transforming society, then we lost the money that we thought we were receiving as compensation for our obedience to power during the Cold War. As the money now slips away, what the "realists" won't tell you, because they have synchronized their minds with the interests of the powerful and the techniques of the technocrats, is we can as communities, through existing laws and technologies, take control of the resources we need to live and thrive in locally. As for the realists, whose dark cynicism constantly undermines us and casts in shade the local in favor of their fantastic visions about benevolent governments in distant capitals, of corporate tigers who can change stripes on a path of redemption, or the impossibility of challenging our laws of trade, always "The 'real' is the enemy of the possible."

No comments:

Post a Comment